Today we publish a conceptual review on loneliness led by the Culture and Sport Evidence team. Our Wellbeing Analyst, Silvia Brunetti, talks about how the review explored the concept of loneliness and what this means in practice. It builds on the review of reviews on loneliness we published last October, which identified confusion in the research, policy and practice communities in defining loneliness in a clear and meaningful way.

The conceptual review looked at studies published worldwide since 1945 and found 144 qualitative sources conceptualising loneliness across the adult lifecourse (16+). The included studies conceptualised loneliness in different ways and for diverse populations groups including old people, young people, groups specified by cultural, gender and sexual-orientation, people living with physical and mental illness, homeless people, and prisoners. Studies were conducted in several contexts including in healthcare, education establishments, workplaces, sports and community locations.

Key findings

- Loneliness is different from social isolation, aloneness and solitude. The element of choice when deciding how alone, or not, we want to be is important. It’s easy to overlook, when focusing on reducing loneliness, but solitude was identified as important and positive in a number of the studies. Conflating aloneness, social isolation and solitude with loneliness could lead to ineffective or stigmatising policies or projects.

- The review found three different types of loneliness experienced by different populations:

-

- Social loneliness refers to the perceived lack of quantity as well as quality of relationships.

- Emotional loneliness describes the absence or loss of meaningful relationships that meet a deeply felt need to be recognised and ‘belong’

- Existential loneliness refers to an experience of feeling entirely separate from other people, often when confronted with traumatic experiences or mortality.

In practice, people experience a mix of the above. The three concepts are not mutually exclusive and there are overlaps between them.

- It’s important to consider all the facets of a person’s situation – gender, sexuality, ethnicity, physical ability, and so on – to develop a nuanced understanding of how loneliness is experienced. For example, the review found female immigrants who were on long-term sick leave from work showed that existential loneliness was the triple feeling of being locked inside one’s home; detached from one’s country of origin; and rejected in the workplace.

Download the slide deck detailing the loneliness findings across the lifecourse for young people and mid life adults.

What does this mean in practice?

How we talk about loneliness influences decisions

The review looked at differences in concepts and language used in research and practice. The aim was to identify and address the complexities associated with loneliness for different people.This is incredibly important because the way we talk about loneliness influences decisions about how best to alleviate loneliness across peoples’ lives.

More research, policy and practice needed on all across loneliness types

There is a large body of research on conceptualising social loneliness which reflect the way in which we think about loneliness and how we act upon it. However, emotional and existential aspects of loneliness are fundamental and should be taken into account both in terms of research and measurement but also when designing policies, programmes, interventions etc. Therefore, there is scope in research, policy and practice to explore in more detail the different types of loneliness and their interrelationships to understand who feels lonely, when, where, in what contexts and what works to help them.

Evidence gaps in relation to younger and mid-life adults

There were no studies that explored concepts of existential loneliness in young people, for example. We’ve outlined all the conceptual findings for these age groups in the lifecourse visualisation, and summarised the extensive findings for older adults detailed in the report. You can find the findings for all age groups in the full report. We are currently compiling the gaps in the evidence from this conceptual review. Look out for a gaps map coming later this year.

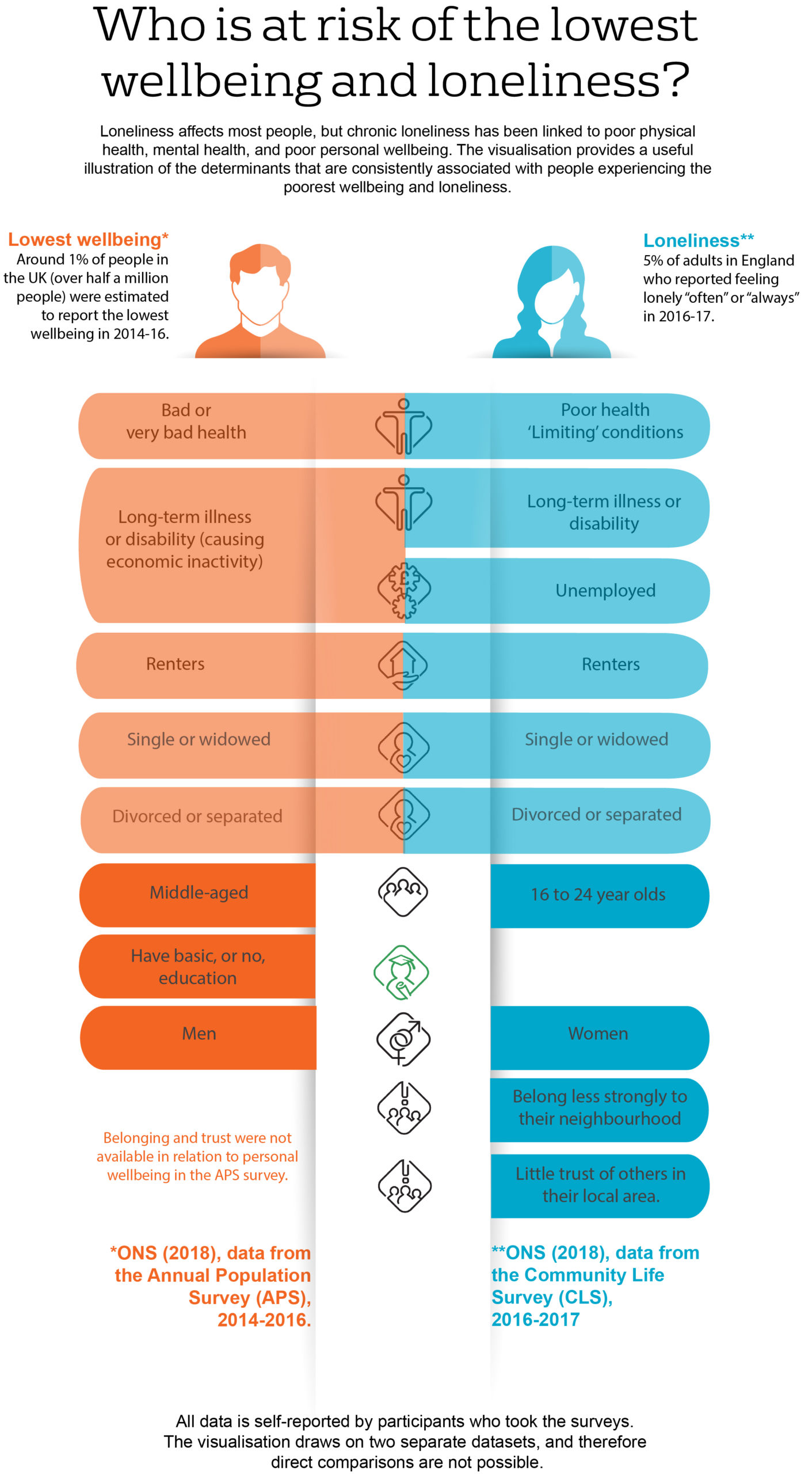

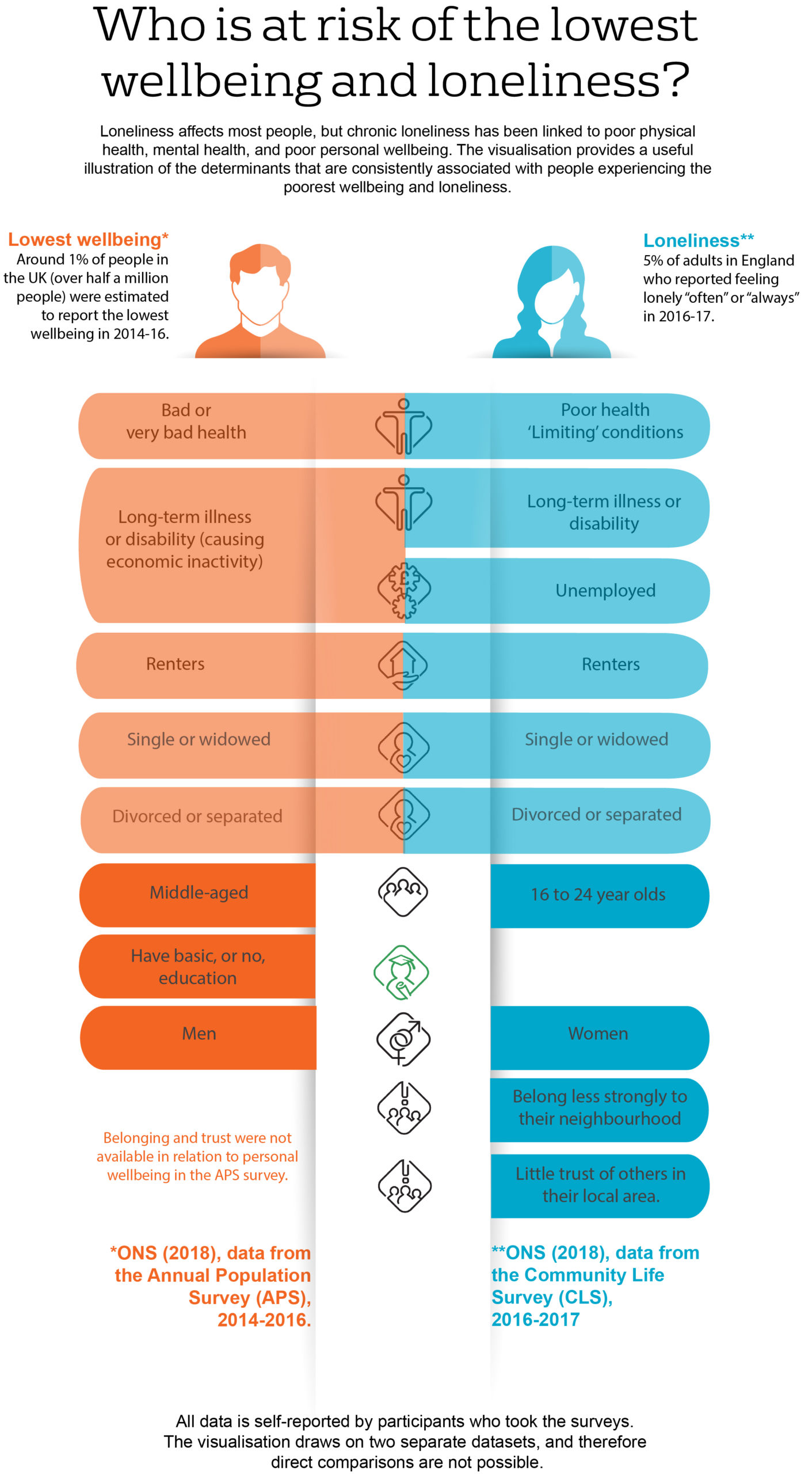

People at higher risk of experiencing loneliness share some similar characteristics with people at risk of lower wellbeing

Such as the role of poor self-reported health – and some differences – like age.

Mansfield L., Daykin N. , Meads C., Tomlinson A., Gray K., Lane J., Victor C. (2019), A conceptual review of loneliness across the adult life course (16+ years). What Works Wellbeing.

Understanding the difference between social isolation and loneliness